ISSN: 0970-938X (Print) | 0976-1683 (Electronic)

Biomedical Research

An International Journal of Medical Sciences

Research Article - Biomedical Research (2017) Volume 28, Issue 3

Spinal fractures as an indicator of concurrent other system injuries: An analysis of 242 cases

1Antalya Education and Research Hospital, Antalya, Turkey

2Ankara Numune Education and Research Hospital, Turkey

3Department of Emergency Medicine, Ankara Numune Education and Research Hospital, Turkey

4Department of Emergency Medicine, Ahi Evran University Education and Research Hospital, Turkey

5Deparment of Neurosurgery, Ankara Numune Training and Research Hospital, Turkey

6Department of Emergency Medicine, Ankara Keçioren Training and Research Hospital, Turkey

Accepted date: July 4, 2016

Introduction: The aim of the present study was to examine any non spinal tissue injuries accompanying spinal fractures in an attempt to determine if spinal fractures are an indicator of the presence, severity, and prognosis of concomitant organ/tissue injuries in two trauma center in Turkey.

Methods: This study had a retrospective cross-sectional design that incorporated the information of the patients presenting to the emergency services of two level 1 trauma centres in the Central Anatolian Region of Turkey between January 2010 and December 2012. Among 242 spinal fracture patients, 98 (41.9%) had accompanying injuries in other regions. Results There was a statistically significant correlation between the accompanying injuries and the single Powered by Editorial Manager® and ProduXion Manager® from Aries Systems Corporation level spinal fractures, the anatomical localization of the spinal fracture (p=0.012, p=0.048). Accompanying injuries associated with Lumbar Spinal Associated Injury (LSAI) were the most common (n=54, 55%) while Servical Spinal Associated Injury (SSAI) were the least common (n=7, 7.14%).

Conclusion: Every patient presenting to emergency department after a high-energy trauma should be regarded as vertebral fracture sunless proven otherwise, and any spine fractures should be taken serious with regard to potential internal organ injuries.

Keywords

Spinal fractures, Associated injuries, Organ injuries.

Introduction

Currently, traumatic injuries constitute a major public health problem and are characterized by high morbidity and mortality rates. Traumatic injury may reflect the injury severity and patient life is more deeply affected by spinal fractures than other types of injuries [1-4].

Vehicular accidents account for approximately one third of reported cases, and approximately 25% of cases are due to violence. Other injuries are typically the result of falls or recreational sporting activities [5].

The spine is protected and supported fairly well by surrounding tissues and organs and only impacts of considerable force that lead to multiple organ injuries are able to cause spinal fractures.

Spine fractures can be accompanied by a wide range of organ/ tissue injuries and emergency physicians should be familiar with and actively sought for the presence of other system traumas and injuries to provide early and directed care when they serve patients with spine fractures [1,6].

Despite the fact that there are several studies that have investigated accompanying tissue/organ injuries with spine fractures, our literature search we found only a single report of systematic studies scrutinizing the accompanying tissue injuries in relation with the anatomical location of spine fractures [3,5-8].

The aim of the present study was to examine any non-spinal tissue injuries accompanying spinal fractures in an attempt to determine if spinal fractures are an indicator of the presence, severity, and prognosis of concomitant organ/tissue injuries in a Level 1 reference trauma center in Turkey.

Materials and Methods

This study had a retrospective cross-sectional design that incorporated the information of the patients presenting to the emergency services of two level 1 trauma centers in the Central Anatolian Region of Turkey between January 2010 and December 2014. The pattern, mechanism, and type of spinal injuries, as well as the demographic properties of patients, accompanying injuries, injury severity score, complications, treatment approaches, and the final outcome were analysed. Injury severity was evaluated using the Injury Severity Score.

The patients were grouped into major, minor, and complex spine fracture groups. Additionally, spinal fractures were grouped as Single Level Spine Fracture (SLSF) and Multilevel Spine Fracture (MLSF). The major spinal fracture group included compression and burst fractures, the minor group involved process fractures, and the complex group contained combined fractures of more than 1 pattern or dislocation.

Medical information obtained via a detailed multiple-variable database was recorded and analysed using the IBM SPSS software version 18. A descriptive analysis of the demographic variables and injury characteristics was performed. Categorical and continuous variables were presented as proportions and mean ± SD. Categorical variables were compared between the groups using the Chi-square test.

Results

Injury demographics and characteristics

Among 242 spinal fracture patients, 98 (41.9%) had accompanying injuries in other regions. Twenty-three (23.4%) of them were female and 75 (76.6%) were male, with a maleto- female ratio of approximately 3.2. The age range of the patients with accompanying injuries was 20 to 81 years. Patients aged 30 to 64 years (n=71, 72%) were most likely to have accompanying injuries in other tissues/systems. Males were significantly more prone to accompanying injuries in other tissues/systems than females (p=0.021). Accompanying injuries were most common with accidental falls (n=47, 47.9%) and least common with occupational injuries summarized in Table 1.

| n | |||

| Spine fracture with associated injury | 98 | ||

| Age | 0-29 | 13 | |

| 30-64 | 71 | ||

| 65-84 | 12 | ||

| ≥85 | 2 | ||

| Gender | Male | 75 | |

| Female | 23 | ||

| Injury mechanism | MVC | 20 | |

| Pedestrian | 10 | ||

| Accidental falls | 62 | ||

| Occupational | 6 | ||

| Localization of spine fracture | Single level | 81 | |

| Cervikal | 7 | ||

| Torachal | 20 | ||

| Lomber | 54 | ||

| Multilevel | 17 | ||

| Injury type | Major (compression+burst fracture) | 74 | |

| Minor (process fracture) | 4 | ||

| Complex (Major+minor) | 20 | ||

| Treatment option | Medical | 28 | |

| Surgical | 70 | ||

| Survey | Mortality | 2 | |

| Morbidity | 8 | ||

Table 1: Epidemiological characteristics of spine fractures with associated injuries.

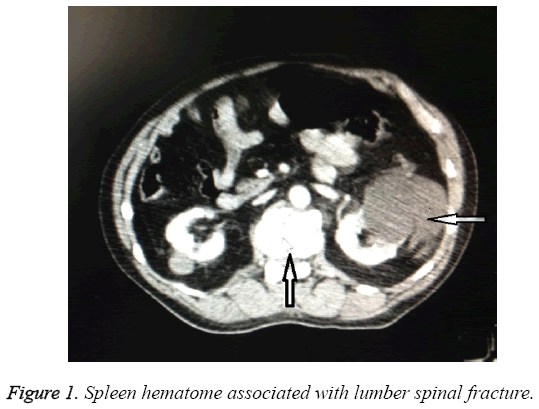

There was a statistically significant correlation between the accompanying injuries and the single-level spinal fractures, and also the anatomical localization of the spinal fracture (p=0.012, p=0.048). Accompanying injuries associated with Lumbar Spinal Fractures (LSAI) were the most common (n=54, 55%) while Servical Spinal Associated Injury (SSAI) were the least common (n=7, 7.14%) as shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

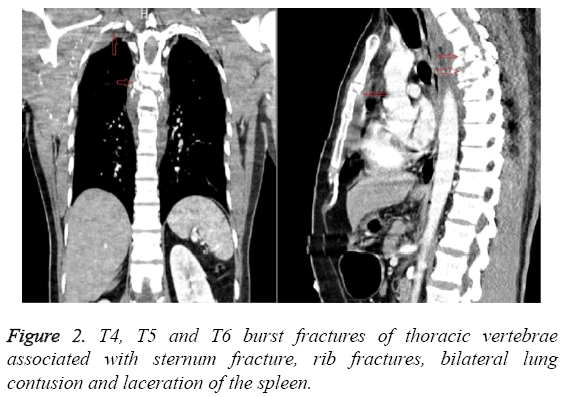

The fracture type and the accompanying injuries were not significantly correlated (p=0.134), but they were more common in compression and burst fractures (n=74, 75.5%). When accompanying injuries to spine fractures are examined, chest and lower extremity injuries (n=36, 36.7%) were the most common accompanying injuries while maxillofacial injuries were the least common (n=5, 6.1%) as shown in Figure 2. There was no significant difference between the anatomical levels of the spinal fractures with respect to the accompanying injuries summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

|

|

Total (n=98) | SLSF | MLSF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chest injury | Rib fracture | 26 | 20 | 6 |

| Pneumothorax | 15 | 11 | 4 | |

| Hemothorax | 13 | 11 | 2 | |

| Pulmonary contusion | 12 | 7 | 5 | |

| Sternum | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Total | 36 | 28 | 8 | |

| Abdominal injury | Spleen laceration/haematoma | 7 | 6 | 1 |

| Renal laceration/haematoma | 7 | 6 | 1 | |

| Liver laceration/haematoma | 6 | 6 | - | |

| Small bowel perforation | 1 | 1 | - | |

| Bladder perforation | 1 | 1 | - | |

| Total | 22 | 21 | 1 | |

| Extremity injury | Radius | 12 | 10 | 2 |

| Clavicle | 3 | 3 | - | |

| Humerus | 2 | 2 | - | |

| Scapula | 2 | 2 | - | |

| Metakarp | 2 | 2 | - | |

| Olekranondislokasyon | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Skafoid | 1 | 1 | - | |

| Ulna | - | |||

| Pelvis | 16 | 14 | 2 | |

| Tibia | 15 | 11 | 4 | |

| Calcaneus | 12 | 9 | 3 | |

| Femur | 8 | 7 | 1 | |

| Fibula | 8 | 6 | 2 | |

| Malleol | 7 | 6 | 1 | |

| Metatars | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Patella | 1 | 1 | - | |

| Total | 47 | 37 | 10 | |

| Head injury | Bony fracture | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| İntracranial haemorrhage | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Pneumocephalus | 1 | - | 1 | |

| Total | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| Maxillofacial injury | Zigoma | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Mandibula | 2 | 2 | - | |

| Pneumoorbita | 1 | 1 | - | |

| Total | 6 | 5 | 1 |

Table 2: Associated injuries in spine fractures.

Injury severity score (ISS)

The range of the Injury Severity Score (ISS) was between 4 and 50 (mean 13.32 ± 8.5 and median 9). A hundred and fiftysix (64.5%) cases had minor injuries (ISS=1-9), 38 (15.6%) had moderate injuries (ISS=10-15), 28 (10.7%) had severe injuries (ISS=16-25), and 22 (8.9%) had profound injuries (ISS>25). The correlation between ISS and duration of hospital stay was positive and statistically significant (rs=0.382, p<0.01). The duration of hospital stay was prolonged as ISS increased.

Survey

The mean duration of hospital stay was 8.72 days (1-60 days). 138 (57%) of patients with spinal fractures were managed surgically. Of the patients with associated injuries two patients died; one of them was due to cerebrovascular event, the other was due to massive pulmonary thromboembolism and the mortality rate was 0.8%. Twelve patients recovered with sequelae and the morbidity rate was 5%. While there was no any statistically significant relationship between survey and associated injuries (p=0.158), morbidity was more frequently observed in spinal fractures with associated injuries (n=8. 8.1%).

Discussion

Traumatic injuries are the most common cause of death among young people [9,10]. Although spinal fractures represent only a minority of injuries suffered by all trauma patients, their influence on the social and financial well-being of the patient is often more significant than that of other injuries [5,10]. Spinal and spine-related other injuries, which are common in highenergy trauma, have the poorest functional outcomes and the lowest rates of return to work among all major organ system injuries [5,6,11-13].

Vertebral column fractures reportedly occur in young middleaged (15-35 years) persons and these fractures are 2 to 4 times more common in males than females [12,14-16]. Yang et al. [14] reported an average age of 31.3 years, Krompinger et al. [15] 34.6 years, and Erturer et al. [11] 30.4 years. Recently, In another a comprehensive study carried out by Wang et al. [5] reported the study group (3142 patients) consisted of 2058 male (65.50%) and 1084 female patients (35.50%). The overall male-to-female ratio was 1.9:1, the mean age of patients with spinal fractures was 45.7 years and the highest rate of spinal fractures was observed in the patients aged 31-40 years. Likewise, our patients had a mean age of 32.3 years, 23 (23.4%) patients were female and 75 (76.6%) were male, with a male-to-female ratio of 3:2.

Studies about the injury mechanisms of the spinal traumas revealed that traffic accidents account for approximately one third of reported cases, and approximately 25% of cases are due to violence. Other injuries are typically the result of falls or recreational sporting activities [1,6,9,14,16]. Wang et al. [5] reported accidental falls were the most common accident mechanism resulting in spinal fractures, and traffic accidents were the second most common mechanism of spinal fracture. Cumulatively, falls and Traffic accidents accounted for 79.79% of the causes of all spinal injuries in the study population.

The resulting axial loading on spinal column leads to axial fractures including the lumbar spine, long bones, and pelvic regions. A lower extremity fracture following a suspicious axial loading injury should prompt investigations for thoracolumbar spinal fractures [6,17]. In falls from a height, calcaneus and tibial fractures are the most common fractures [12,18,19]. According to our results, pelvis was the most common (n=16.34%) accompanying pathology. We believe that the higher rate of pelvic fractures among the accompanying lesions is a direct result of a higher incidence of falls from a height in patients with spinal fractures. Sports and domestic injury-related injuries have been increasing recently [5,20,21], although we did not encounter those mechanisms as the culprit etiology.

The accompanying injuries to vertebra fractures has been reported to range between 43% and 78%, with head, chest, and long bone injuries being the most common ones. Internal organ injuries have been reported to be most common with thoracic region fractures [6,11,12,16,22]. Wang H et al. [5] reported the prevalence of associated injuries was 30.36%. Thoracic injuries were the most common associated injuries, Followed by lower-extremity injuries. We detected accompanying injuries in 98 (41.9%) cases.

Cervical vertebrae are small structures with a high range of motion, and they are prone to be injured or broken by less force and with fewer accompanying injuries compared to the other parts of spine [6]. In patients with cervical vertebral fractures; serious injuries as head and maxillofacial injuries [17,23-26], vertebral artery injury [27,28], tracheal and oesophageal rupture may occur [29]. In our study, chest injuries were also the dominant concominant injury so cervical spine fractures should be further investigated in detail to detect rapidly any potential life-threatening associated injury.

Anatomic stability offered by rib articulations appears as a result of the fact that 82% of thoracic spine injuries had accompanying injuries in other tissues. A statistically nonsignificant one third of thoracic spine fractures were associated with chest trauma. Studies have suggested that owing to those firm and strong anatomical connections thoracic spine fractures may be more commonly associated with rib fractures, lung, heart, oesophagus, and other vascular injuries [6,30-33]. In our study, consistent with the literature, 45% of patients with thoracic vertebral fractures had rib fracture and 35% had pneumothorax.

Lumbar vertebrae are thick and anatomically firm structures, thus a considerable force is required to sustain fractures to them. Additionally, these vertebrae are anatomically adjacent to abdominal viscera and thus prone to co-occur with injuries to abdominal organs in patients with lumbar fractures [6,7]. In a study conducted with 92 patients with lumbar transverse process fracture; 19 had hepatic injury, 12 had splenic injury, 5 had colon injury, 51 had urinary tract injury and in 32 patients had thoracic-orthopaedic-maxillo-facial and cerebral trauma. Observed mortality rate was 11% [34]. Hence, our study demonstrated that lumbar spine fractures were the most common fractures that were associated with abdominal organ injury (11.4%). The spleen, kidney, liver and small bowel were the most commonly injured organs as in the literature. Similar organ distribution has been reported in literature for blunt trauma [12,35]. These data suggest that lumbar injuries should be further investigated in detail to detect any potential abdominal injury [12]. In our study it was interesting that various retroperitoneal organs, such as pancreas and duodenum, were spared from being injured despite their close anatomical relationship with lumbar spine.

Multilevel Vertebral Fractures (MLVF) cause more associated injuries/fractures than SLSF, possibly owing to a higher force requirement to sustain multi-level vertebral fractures [7]. To our surprise, however, our study showed a statistically significant relationship between single-level fractures and associated injuries, possibly because of the small number of MLVFs.

Our study suggested a worse prognosis associated with simultaneous injuries with spine fractures; the number of the accompanying injuries with an ISS ≥ 16 that indicated more serious injuries was 48 (48.9%). However, in our study traumatic spinal injuries were associated with lower hospital mortality, possibly because of a multidisciplinary, wellorganized approach to trauma cases in our emergency department.

This study has some limitations. The variable sample size of the population groups is one of them. As such, majority of patients belonged to the adolescent age group. Ideally, one would expect that the injuries would have been similarly if not equally distributed between all age groups. Nevertheless, this was a retrospective cross-sectional study that used information of consecutive patients with spinal fractures and it probably reflects age distribution of spinal fractures more accurately and realistically.

Conclusion

In this study, vertebral fractures were commonly associated with injuries to other organs or tissues of human body. Thus, such patients should be thoroughly investigated for the presence of accompanying injuries. Every patient presenting to emergency department after a high-energy trauma should be regarded as vertebral fractures unless proven otherwise, and any spine fractures should be taken serious with regard to potential internal organ injuries and every attempt should be made to rule out potentially fatal internal organ injuries upon detection of these fractures.

Ethical Standards

All authors obey the rules of Helsinki Declaration and no ethic problem exists in the manuscript.

References

- Heidari P, Zarei MR, Rasouli MR, Vaccaro AR, Rahimi-Movaghar V. Spinal fractures resulting from traumatic injuries. Chin J Traumatol 2010; 13: 3-9.

- Leucht P, Fischer K, Muhr G, Mueller EJ. Epidemiology of traumatic spine fractures. Injury 2009; 40: 166-172.

- Singh R, Mc DTD, DSouza D, Gorelik A, Page P, Phal P. Injuries significantly associated with thoracic spine fractures-a case-control study. Emerg Med Australas 2009; 21: 419-423.

- T Durdu, C Kavalci, F Yilmaz, MS Yilmaz, ME Karakiliç, ED Arslan. Analysis of trauma cases admitted to the emergency department. J Clin Anal Med 2014; 5: 182-185.

- Wang H, Zhang Y, Xiang Q, Wang X, Li C, Xiong H. Epidemiology of traumatic spinal fractures: experience from medical university-affiliated hospitals in Chongqing, China, 2001-2010. J Neurosurg Spine 2012; 17: 459-468.

- Saboe LA, Reid DC, Davis LA, Warren SA, Grace MG. Spine trauma and associated injuries. J traum 1991; 31: 43-48.

- Rabinovici R, Ovadia P, Mathiak G, Abdullah F. Abdominal injuries associated with lumbar spine fractures in blunt trauma. Injury 1999; 30: 471-474.

- Xia T, Tian JW, Dong SH, Wang L, Zhao QH. Non-spinal-associated injuries with lumbar transverse process fractures: influence of segments, amount, and concomitant vertebral fractures. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013; 74: 1108-1111.

- George MG, James SH, Zachary JS. Vertebral fracture. Medscape 2016.

- Arslan ED, Kaya E, Sonmez M, Kavalci C, Solakoglu A, Yilmaz F. Assessment of traumatic deaths in a level one trauma centerin Ankara, Turkey. Eur J Trauma EmergSurg 2015; 41: 319-323.

- Erturer E, Tezer M, OzturkI, Kuzgun U. Evaluation of vertebral fractures and associated injuries in adults. ActaOrthopTraumatolTurc 2005; 39: 387-390.

- Wang H, Zhou Y, Ou L, Li C, Liu J, Xiang L. Traumatic vertebral fractures and concomitant fractures of the rib in southwest china, 2001 to 2010-An Observational Study. Med Baltmre 2015; 94: 1985.

- Pirouzmand F. Epidemiological trends of spine and spinal cord injuries in the largest Canadian adult trauma center from 1986 to 2006. J Neurosurg Spine 2010; 12: 131-140.

- Yang Z, Lowe AJ, Harpe DE, Richardson MD. Factors that predict poor outcomes in patients with traumatic vertebral body fractures. Injury 2010; 41: 226-230.

- Krompinger WJ, Fredrickson BE, Mino DE, Yuan HA. Conservative treatment of fractures of the thoracic and lumbar spine. OrthopClin North Am 1986; 17: 161-170.

- Matejka J,15Zeman J, Belatka J, Nepras P, Houcek P, Linhart M. Seat-belt and change fractures of the thoracolumbar spine. ZentralbiChir 2010; 135: 149-153

- Freeman MD, Eriksson A, Leith W. Head and neck injury patterns in fatal falls: epidemiologic and biomechanical considerations. J Forensic Leg Med 2014; 21: 64-70.

- Saifuddin A, Noordeen H, Taylor BA, BayleyI. The role of imaging in the diagnosis and management of thoracolumbar burst fractures: current concepts and a review of the literature. Skeletal Radiol 1996; 25: 603-613.

- Walters JL, Gangopadhyay P, Malay DS.Association of calcaneal and spinal fractures. J Foot Ankle Surg 2014; 53: 279-281.

- Allan DG, Reid DC, Saboe L. Off-road recreational motor vehicle accidents: hospitalization and deaths. Can J Surg 1988; 31: 233-236.

- Lee EJ, Lee JS, Kim Y, Park K, Eun SJ, Suh SK, Kim YI. Patterns of unintentional domestic injuries in Korea. J Prev Med Public Health 2010; 43: 84-92.

- Beaunover M, Vil D, Lallier M, Blanchard H. Abdominal injuries associated with thoraco-lumbar fractures after motor vehicle collision. J Pediatr 2001; 36: 760-762.

- Hills MW, Deane SA. Head injury and facial injury: is there an increased risk of cervical spine injury. J traum 1993; 34: 549-553

- Kobayashi K, Imagama S, Okura T, Yoshihara H, Ito Z, Ando K. Fatal case of cervical blunt vascular injury with cervical vertebral fracture: a case report. Nagoya J Med Sci 2015; 77: 507-514.

- Mukherjee S, Revington P. Cervical spine injury associated with facial trauma. British J hosp med 2014; 75: 331-336.

- Paiva WS, Oliveira AM, Andrade AF, Amorim RL, Lourenco LJ, Teixeira MJ. Spinal cord injury and its association with blunt head trauma. Int J Gen Med 2011; 4: 613-615.

- Cothren CC, Moore EE, Biffl WL, Ciesla DJ, Ray CE, Johnson JL, Moore JB, Burch JM. Cervical spine fracture patterns predictive of blunt vertebral artery injury. J trauma 2003; 55: 811-813.

- Schwarz N, Buchinger W, Gaudernak T, Russe F, Zechner W. Injuries to the cervical spine causing vertebral artery trauma. J traum 1991; 31: 127-133.

- Reddin A, Mirvis SE, Diaconis JN. Rupture of the cervical oesophagus and trachea associated with cervical spine fracture. J traum 1987; 27: 564-566.

- Cotton BA, Pryor JP, ChinwallaI, Wiebe DJ, Reilly PM, Schwab CW. Respiratory complications and mortality risk associated with thoracic spine injury. The Journal of trauma 2005; 59: 1400-1407

- Yang R, Guo L, Wang P, Huang L, Tang Y, Wang W. Epidemiology of spinal cord injuries and risk factors for complete injuries in Guangdong, China-a retrospective study. PLoS One 2014; 28; 9: 84733.

- Petitjean ME, Mousselard H, Pointillart V, Lassie P, Senegas J, Dabadie P. Thoracic spinal trauma and associated injuries: should early spinal decompression be considered. J traum 1995; 39: 368-337

- Westhoff J, Kalicke T, Muhr G, Botel U, Meindl R. Thoracic injuries associated with acute traumatic paraplegia of the upper and middle thoracic spine. Chirurg 2005; 76: 385-390.

- Sturm JT, Perry JF. Injuries associated with fractures of the transverse processes of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae. J traum 1984; 24: 597-599.

- Muller CW, Otte D, Decker S, Stubig T, Panzica M, Krettek C, Brand S. Vertebral fractures in motor vehicle accidents: a medical and technical analysis of 33,015 injured front-seat occupants. Accid Anal Prev 2014; 66: 15-19.